Abstract

Although accreditation standards expect that the curriculum of U.S. schools of social work be informed, in part, by the professional practice community, there has been limited scholarly attention to how schools can assess and respond to curricular expectations from the field. This case study provides one example of practicum partners informing curriculum revision. Although this case study describes an assessment process, the focus of this paper is on the practice of engaging practicum partners in the assessment, rather than on reporting the findings of the assessment research. We describe how the program engaged practicum partners, key learnings from the field, and the curricular changes informed by the process.

Keywords: curriculum development; practicum partners; professional practice community

Practicing Reciprocity: A Case Study of Practicum-Engaged Curriculum Revision

There is an expectation of reciprocity between schools of social work and social work agencies. Within a given agency, students contribute to the organizational mission while gaining supervised experience and professional development (Pelech et al., 2009). More broadly, schools of social work rely on agencies to provide the educational practicum placements students must complete as part of their social work training. In turn, agencies rely on schools of social work to build workforce capacity in their region. Although accreditation standards set forth by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) expect that social work educational programs are “informed by the professional practice community” and require schools to “explain how the professional practice community is engaged and the impact this engagement has on curriculum content, development, and delivery” (CSWE, 2025, p. 21), CSWE does not mandate the manner in which schools engage the practice community. In reality, despite the mutual reliance between colleges and agencies, their relationship is somewhat uneven. Whereas schools set numerous expectations of practicum partners (i.e., related to the kinds of learning experiences expected in practicum sites, forms to complete, requirements of supervision), there are fewer opportunities for practicum partners to influence schools of social work, particularly regarding the curriculum (Lewis, et al., 2016; Morris et al., 2024). One reason for the reticence to engage practicum partners in deliberation about the curriculum may be the ongoing tension regarding the function of social work education.

What is the Role of the Field in Social Work Education?

There is an ongoing question regarding the role of social work education: Should schools of social work serve to prepare students for the world as it is, to practice knowledgeably and effectively within existing systems or care; or should schools prepare students for the world as it could be, to challenge, transform, and otherwise reimagine social work and the meeting of social welfare needs in their communities (Dalton & Wright, 1999; Reisch, 2013)? Given the degree to which many existing social welfare systems at best reform, but often reproduce, systemic inequities, this remains a critical question. Those concerned about such reproduction may be wary of how much power practicum partners have in shaping the curriculum. Indeed, as Mehrotra et al. noted, “Practicum education may reinforce roles in which social workers act as neoliberal agents rather than change agents … because it is the only thing they are exposed to, or it is seen as the only viable avenue to employment in the field” (Mehrotra et al., 2018, p. 137).

While we share these concerns, we are also troubled that this tension between preparing social workers for the “world as it is” and “the world as it could be” is predicated on the assumption that innovation and transformation only and always emerge from universities, and that practicum placements, in contrast, are only and always complicit with the status quo. Clearly, innovation potential exists both within academic institutions and in the field, and social work students may be as likely to encounter outdated theoretical and practice models and neoliberal ideologies in the classroom as in the field. Thus, this false binary is not reason enough to exclude practicum partners from informing the curriculum. Further, given social work’s ethical commitment to collegial consultation (National Association of Social Workers, 2021), schools of social work could consider practicum partners as critical collaborators with valuable insight into the needs of a given community, which in turn could inform the curriculum.

Examples of Practicum Collaboration in Curriculum Development

To find examples of how schools of social work engage the field in their curriculum development efforts, we conducted a search within the 27 Proquest databases using the search parameter “(‘curriculum’ AND ‘social work’) AND (‘field’ OR ‘practicum’)” occurring in abstracts of articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 1995 and 2024. We reviewed each abstract, and if it appeared that the article might describe community-engaged curricular development (which we defined as any attempt to understand what practicum partners or local social service provides believed students should learn), we reviewed the article in full.

Overall, there is a dearth of scholarship in this area. We found only three examples of schools of social work that engaged the field to inform their curriculum as a whole (Cronin et al., 2021; Dalton & Wright, 1999; Morris et al., 2024). There are more examples of schools of social work that have assessed practicum partners’ expectations related to a particular curricular area, such as macro practice (Mehrotra et al., 2018; Sousa et al., 2020), gerontology (McCaslin & Barnstable, 2008), interdisciplinary practice (Garcia et al., 2010), and integrating a trauma-informed and human rights perspective (Lewis et al., 2016). Several other schools are actively collaborating with local field professionals to collaborate in the development and provision of targeted curricula, such as in concentrations focused on working with tribal communities (Greenwood & Palmantier, 2003; Haight et al., 2019) or serving unhoused populations (Gallup et al., 2023).

Cronin et al. (2021) provided an innovative example of a multiyear curriculum revision process rooted in reciprocity at California State University Fresno. As they wrote, “If we wanted to build a curriculum that really addressed community needs, then we needed to gather data on those needs” (p. 60). Faculty integrated a participatory action research project into BSW and MSW research courses wherein students gathered and analyzed feedback from practicum partners, and results were used to inform curriculum revisions. Importantly, in the three examples of community-engaged curriculum revision, while practicum partners contributed critical insight into the local context and expectations of emerging social work practitioners, faculty had the ultimate responsibility for determining the curriculum. As Dalton and Wright (1999) explained, “Not all of the issues raised have been addressed by the planned curriculum changes, nor will all of them be. The faculty must consider seriously the desires of the community… balanced with other professional considerations” (p. 287). In other words, while schools of social work are ultimately responsible for crafting their curriculum, practicum partners can meaningfully contribute to the process of doing so.

A Values-Based Approach to Community-Engaged Curriculum Development

Rather than propose a particular method of community-engaged curriculum development, we propose that schools of social work adopt a values-driven approach. Principles of feminist community engagement may be instructive in this regard, as they emphasize relationships of reciprocity and accountability (Iverson & James, 2014; Sheridan & Jacobi, 2014), which align with existing social work values (CSWE, 2022). Schools of social work may typically consider reciprocity and accountability as values that students should demonstrate in their practicum placements and other forms of service learning (Twill et al., 2011), and underestimate the need for faculty to also bring a commitment to these values in their relationship with the field.

Two implications follow from such a commitment. First, in social work programs the decision of what and how to teach requires more than the expertise garnered through the faculty’s educational and professional background. Second, engagement with social work practitioners in educators’ own communities can enrich their understanding of the needs of the field and how best to prepare future practitioners to meet those needs. In practice, reciprocity with the field requires that social work educators ask a number of critical questions:

- What do practicum partners expect social work students to know, and know how to do, as they begin their social work practicums?

- What knowledge and skills do they expect social work students to graduate with?

- To what degree are these expectations aligned with those that faculty have for students?

- If there is misalignment, how might this be resolved to better prepare our students for practice, and/or to better prepare our practicum partners for students?

And, once these questions are asked, reciprocity requires that social work educators take seriously what they learn, and consider how these answers might inform the curriculum.

To explore how schools of social work can enact reciprocity with practicum partners, we offer the following case study of a community-engaged curriculum revision process. As a practice-focused article, this case is intended to illustrate our experience of engaging practicum partners, specifically:

- How did the program engage practicum partners?

- What did the program learn from this engagement?

- What changes were informed by this learning?

In contributing to the scant literature in this area, we aim to expand possibilities for how schools of social work might enhance their relationships with practicum partners and ultimately improve the quality of social work education by increasing responsiveness to their local context.

Case Study Context

At an access-focused public university in the Pacific Northwest, the Master of Social Work (MSW) program partners with over 400 agencies, providing a total of 222,500 student-hours per year. The program includes a generalist foundation-year curriculum, and all students select between clinical or macro practice concentrations in their advanced year. In the fall of 2018, the MSW program chair launched a three-year curriculum renewal process. While aspects of this process will be detailed below, the renewal process generally followed four phases of activity. First, faculty reviewed the core MSW courses and provided substantive feedback about course strengths, limitations, and opportunities for improvement. Second, a team of faculty and a doctoral student (including both authors) engaged practicum instructors and task supervisors regarding their expectations of the program’s curriculum, using surveys (N = 135) and interviews (N = 20). Next, the chair surveyed MSW instructors (N = 38) about their expectations of the curriculum. Findings from these surveys and interviews were integrated into a report and shared with the full faculty, students, and practicum partners (Thurber & Halverson, 2021). Finally, results were used to make program-level curricular changes, as well as to inform changes to individual courses.

Concurrent with the start of the curricular renewal process, Author 1, a member of the faculty, collaborated with colleagues to design this study of the curricular renewal process and outcomes (which the IRB determined to be exempt). This case study (Simons, 2014) draws on data gathered from practicum and faculty members, process artifacts, and reflections from faculty who participated in the course revision process, to examine the community-engaged aspects of the curriculum development process.

Findings

The case is organized around three broad questions: How did the program engage practicum partners? What did the program learn from this engagement? What changes were informed by these learnings? In the first section, we describe the strategies used to engage practicum partners in the curriculum revision process and reflect on the effectiveness of these strategies. Second, we identify key learnings from the field, as well as the alignment—and misalignment—between field expectations of the curriculum and the expectations of faculty. Third, we describe the curricular changes that this process informed.

How Did the Program Engage Practicum Partners?

Engagement Methods

A team of three faculty members (including the MSW program chair, the director of practicum education, and Author 1) and a doctoral student (Author 2) developed a proposal to engage practicum instructors and task supervisors in the curriculum renewal process. We intended to assess the degree of alignment between the MSW curriculum and the needs of practicum partners, and, if applicable, to identify ways to enhance that alignment through curriculum revisions.

The team developed an electronic survey, and in the summer of 2020 distributed it to everyone who had served as a practicum instructor and/or task supervisor in the 2019-2020 academic year. The survey contained both fixed-choice and open-ended questions, with responses optional to most questions. Questions elicited the most common theories and practice approaches in use among practicum sites; expectations of student competence in their generalist placement, advanced placement, and at graduation; and perceptions of student readiness for advanced practice overall, and for racial equity work in particular (for survey details, see Thurber and Halverson, 2021). After sending three reminders over four weeks, the online survey was closed.

The survey was completed by 135 respondents, for a 32% overall response rate. The vast majority of respondents (91%) were on-site practicum instructors; the remainder identified as task supervisors or off-site practicum instructors. Practicum instructors and task supervisors from all modalities (on-campus, distance, and online) and concentrations participated in the survey. After cleaning the data, we used descriptive statistics to understand trends, and similarities and differences by concentration.

The final survey question asked respondents to share their contact information if they were interested in being contacted about a more in-depth interview, and 45 respondents did so. We selected interview participants (n = 20) in waves to ensure representation from all MSW program options and concentrations. We also prioritized respondents of color to increase racial diversity in our interview sample. Interview questions elicited respondents’ reflections about student readiness for practicum and future employment, student preparation for racial justice work, the relevance of curriculum and assignments to the practicum, and expectations for students’ research preparation. Author 2 conducted interviews via Zoom from August to October 2020, with recordings (created with the Zoom recording and transcription functions) ranging from 25 to 63 minutes long. Almost all (n = 18) interviewees were on-site practicum instructors, and fewer than half (n = 8) identified as BIPOC and/or multiracial. After participating in the interview, interviewees received a $20 electronic gift card.

Author 2 cleaned and uploaded the transcripts into qualitative analysis software (MaxQDA) and coded the transcripts using interview questions as temporary parent codes. She then combined the coded interviews with similarly-coded open-ended responses from the survey. After Author 2 created draft themes from the codes, the two authors talked through the findings to identify the findings most applicable to the curriculum revision process to highlight in a report sent to program leadership, faculty, staff, practicum instructors, and students.

Reflections on the Engagement Process

Our 32% overall response rate is lower than the average 44% online survey response rate in published research (Wu et al., 2022), yet we found the sample to be representative in terms of concentration and location, with all subgroups having at least a 29% response rate. We were generally satisfied with the response rate to both the survey and invitation to be interviewed, particularly as we launched this engagement relatively early in the pandemic, when many of our practicum partners were still functioning in extraordinary, and extraordinarily challenging, conditions. We are also pleased with the interview sampling protocol, which facilitated intentional engagement with practicum partners regarding insights into different aspects of the curriculum. However, we regret the decision to leave racial identification optional. Our program has a strong racial justice focus, and understanding how practicum partners perceive the effectiveness of this curriculum was a priority. The school has developed practicum placements at a number of culturally specific organizations, and we hypothesized that practicum partners who work in these settings, and/or identify as Black, Indigenous, Latina/o/e/x, Asian, Pacific Islander and/or as a person of color (BIPOC) might view our racial justice curriculum differently than White respondents. While we hoped to analyze answers with this in mind, we also wanted practicum instructors to be able to self-identify their racial and/or ethnic identity, and so we created this as an optional text-entry field. Unfortunately, 35% did not identify their race or ethnicity, limiting our ability to make meaningful between-group comparisons in the survey analysis.

What Were Key Learnings?

For the purposes of this case study, this section hones in on findings that were most salient to the curriculum renewal process. The surveys and interviews with practicum partners affirmed three key strengths of the MSW curriculum to sustain, as well as three areas of vulnerability in the curriculum to bolster.

The first strength is the alignment of the generalist curriculum to practicum partner expectations. Through the survey of practicum instructors, we learned that of the 19 content areas included in the generalist year, all but four aligned with most practicum partners’ expectations of what students should learn (for a detailed review of the results, see Thurber and Halverson, 2021). In addition, more than 80% of survey respondents (and most interviewees) indicated that our MSW students are prepared for practicum placements.

A second strength of the curriculum is the preparation of students to engage in critical thinking and ethical decision-making. More than 90% of survey respondents reported that our students adhere to professional ethics, and have the skills, knowledge, and theoretical base to be employable following graduation. Practicum instructors also emphasized students’ critical thinking abilities, offering comments such as “students are critical thinkers, questioners, able to take in new information and use it to inform practice,” and “intellectually capable of critical thinking.” Notably, students’ critical thinking and ethical decision-making skills met or exceeded most practicum partners’ expectations.

Finally, the survey affirmed a number of areas where the curriculum was playing a particularly vital role in preparation for practice. The survey asked practicum partners who work in both clinical and macro practice settings to consider their expectations of advanced students, and indicate what skills and knowledge they expect students to have before starting an advanced placement, the competencies students will likely develop during their placement, and the competencies students should graduate with, whether or not they will practice them in the respondent’s agency. In both clinical and macro settings, this subset of questions illuminated competencies that, while expected by future employers, students are unlikely to practice in their practicum placement.

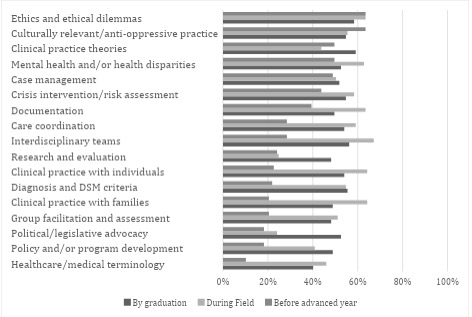

For example, among respondents working with clinical students, it was not surprising that clinical practice theories, diagnosis and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) criteria, clinical practice interventions with individuals, and crisis intervention/risk assessment were among the most frequently selected knowledge and skills expected of graduates. Ethics and ethical dilemmas, interdisciplinary teams, and culturally relevant/antioppressive practice were also frequent responses. As indicated in Figure 1, students are likely to gain knowledge and skills in many of the advanced competency areas in most placements. Notable exceptions are research and evaluation, and legislative advocacy, which suggests that clinical students will develop competency in these areas through coursework rather than practicum placements.

Figure 1

Practicum Expectations of Advanced Clinical Students’ Knowledge Acquisition

In addition to revealing the critical role of the curriculum in some content areas, survey data also made evident content areas that could be shifted later in the curriculum. While the majority of practicum partners expect students to enter the advanced year with competency in social work ethics and culturally relevant and antioppressive practice, in most other advanced competency areas, practicum partners anticipate that students will develop knowledge and skill throughout the placement (see Figure 1). In most areas, respondents indicated that clinical students will develop the knowledge and skills they expect them to graduate with during the advanced year practicum placement.

More than half of respondents who work with macro students expect students to graduate with equity assessment and analysis, fiscal analysis and budgeting, macro practice theories, research and evaluation, political or legislative advocacy, and community assessment skills (see Figure 2). Students are likely to gain knowledge and skills in many of the advanced competency areas in most placements. However, there are several areas that students are unlikely to practice in a majority of practicum placements: fiscal analysis/budgeting, political/legislative advocacy, and to a lesser extent, community and/or labor organizing. This suggests that macro students will develop competency in these areas through coursework, rather than practicum placements.

Figure 2

Practicum Expectations of Advanced Macro Students’ Knowledge Acquisition

The most significant gaps identified by practicum partners relate to direct practice skills. While in surveys most respondents indicated that students are generally prepared for practicum education, a more nuanced picture emerged in interviews with clinical practicum instructors. Nearly all (11 of 12) clinical practicum instructors reported that students do not begin with adequate mental health direct practice skills. An interviewee explained,

My advanced practice students I’ve had in the past have been sort of … terrified about even … doing a family therapy session. Feeling like they’re just—they haven’t been equipped at all with … conceptually what it means to hold space for a family or what it means to do the initial … how do you just start an individual session with somebody, … how do you just … do that unless it’s just … conversational stuff? Yeah, and … doing a biopsychosocial assess[ment] …the interview itself, not the writing, … but … the actual face-to-face work causes a lot of anxiety for most students.

Additionally, four interviewees indicated that some students need stronger professional skills, for example, related to workplace expectations for oral and written communication. These respondents desire more attention to direct practice and professional skills earlier in the program.

A second vulnerability in the curriculum is uneven preparation for antiracist practice. Results in this area were mixed. Sixteen survey respondents identified justice (social justice and/or racial justice) as a strength of the curriculum, noting, “I believe [university] MSW students are highly capable and skilled around organizing and at identifying and entering in discourse around racial justice, environmental justice, and related topics,” and “I think for the students that I’ve worked with from [university], especially from the School of Social Work, is that they have the ability to advocate for our community and understanding of racial justice and racial equity.” As noted previously, more than a third of respondents did not indicate their race or ethnicity, limiting our ability to fully assess differences based on respondents’ demographics. Although 70% of respondents overall indicated that students are prepared for antiracist practice, only 57% of those who identified as BIPOC agreed with this assessment. Six survey respondents identified antiracist work as a gap in the curriculum. Comments included the need for “more attention to antiracist and inclusive practice”; that “students have reported to me not feeling like they are receiving enough culturally-competent and antiracist curriculum”; and a desire for “antiracism and exploring more white supremacy in social work history and present day.” Although most practicum instructors were satisfied with how the school prepares students for racial equity work, the mixed results suggest that attention to racial and social justice is an area of strength in the curriculum and could be enhanced.

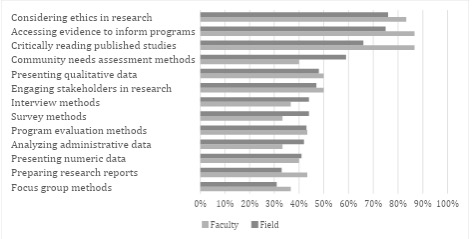

A final vulnerability identified from this analysis relates to the research curriculum, which has historically included a two-course sequence that emphasizes quantitative study design. The surveys distributed to both practicum partners and to faculty included a subset of questions related to expectations of students’ research preparation. Both faculty and practicum instructors were asked “How important is it that MSW students graduate with the following research skills?” Faculty chose from one of the following answer choices for each area: very important for all students, very important for some students, or not important). Practicum respondents chose from the following answer choices: very important, somewhat important, or not important. Figure 3 indicates the percentage of faculty who rated each area as“very important for all students”and the percentage of practicum respondents who rated each area as “very important.”

Figure 3

Percentage of Practicum and Faculty Indicating Research Skills as “Very Important”

Although most practicum and faculty members agree that some research competency areas are essential for all MSW graduates, many areas typically included in the curriculum are not expectations of most practicum and faculty (see Figure 3). For example, more than 60% of faculty and practicum respondents agreed that students should know how to access evidence to inform programs or policy, read published studies critically, and consider ethics in research. However, most faculty and practicum respondents do not expect students to graduate with competency in most forms of data collection and analysis. Notably, most faculty identified fewer than half of these areas as necessary for all students. A majority of faculty agreed in only five of the 13 areas that a particular research skill is necessary for all students. The research expectations of practicum instructors and faculty are similar, though not identical (see Figure 3). For example, practicum respondents were more likely than faculty to report that MSW students should graduate with knowledge and skills in conducting community needs assessments. Among practicum respondents, supervisors of macro students were more likely to see all research areas as “very important” than clinical supervisors.

The overwhelming majority of interviewees (n = 16) indicated that graduates should be able to find, critically read, and understand research—but did not expect graduates to be prepared to conduct independent research. An interviewee summarized: “We’re not doing any formal research. Mainly what I need from my students is the ability to know where to find something and how to access it.” Another expressed their expectations this way:

It’s being able to critically read literature and prepare reports that inform decision-making. And to be able to kind of synthesize all of that knowledge and turn it into a recommendation, and then figure out how to give that recommendation to somebody who’s in a position of power, while holding communities at the core.

As reflected in these quotes, the primary use of research in the field is accessing preexisting scholarship to inform client services, programs, and policies.

Taken together, practicum partners’ perspectives on the strengths of the MSW program curriculum, what students should learn in the program (and when that learning is most critical), and the kind of learning and practice that is likely (and unlikely) to occur in practicum placements highlight aspects of the curriculum to keep and/or enhance during the curriculum renewal process. Practicum partners’ reflections on gaps related to direct practice and professional skills, mixed views of students’ preparation for antiracist practice, and the misalignment of the research coursework expectations to needs in the field illuminate aspects of the curriculum to enhance and/or revise during the curriculum renewal process.

What Changes Were Informed by These Learnings?

The team of faculty who lead the MSW program’s core curriculum discussed initial findings from the surveys and interviews with practicum partners, and survey findings with faculty. This team helped identify the implications of findings for the curriculum revision process, which were integrated into a final report (Thurber and Halverson, 2021) and presented to the full MSW faculty. As described below, the findings and implications helped instructors discern what curriculum we should maintain and/or enhance to preserve the program’s perceived strengths, and informed program-wide changes, the revision of some existing courses, and the creation of some new courses. There were also areas where input from practicum partners did not result in changes to the curriculum.

Curriculum to Maintain or Enhance

Faculty committed to maintaining or enhancing areas that practicum partners identified as strengths of the curriculum, including content and assignments that support students’ development as ethical and competent social work practitioners (which is integrated across the curriculum), and contributes to students’ knowledge and skills of social and racial justice (which is the focus of a core course taken by all students, and is also expected to be integrated throughout the curriculum). In response to practicum instructors’ identification of critical competencies that students are unlikely to practice in their practicum (such as fiscal analysis and budgeting, and research and evaluation skills for macro students), instructors preserved and strengthened curriculum in these areas.

Programmatic Changes

Based on the misalignment between research preparation and expectations of both faculty and practicum partners, the faculty redesigned the MSW research preparation. Previously a quantitatively focused two-course research sequence, the new model includes a redesigned generalist course that introduces students to multiple approaches to systematic inquiry in social work, and then provides students with a slate of options for their advanced research course (including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methodology courses). This change accomplishes a number of objectives: The generalist course develops students’ skills in accessing and analyzing preexisting scholarship, which aligns with practicum expectations for graduating MSW students; and the shift from a single statistics course to an array of advanced research offerings provides students more choice/agency in the curriculum, while also providing more faculty the opportunity to teach in their area of methodological expertise and interest.

Based on feedback that attention to justice is both a strength and an area for growth in the school, the MSW program adopted a new model for reviewing new and revised courses. Past processes for reviewing course proposals did not explicitly assess alignment with the stated mission of the MSW program, which is to prepare students for practice “that recognizes and dismantles systems of oppression; builds racial equity and social, political, and economic justice; and advances the well-being of diverse individuals, families, groups, organizations, communities and tribal nations.” The new process asks instructors proposing new courses to describe the course’s key contributions to the program mission, with the intention that this will help ensure that all courses include content, instruction, and or assignments that advance equity and well-being.

Course Revisions

A number of course revisions were completed to enhance preparation for direct practice. Given the expectations of practicum instructors regarding what students need prior to their advanced placement, the program enhanced the focus in the generalist year on direct practice skills with individuals and families, integrating the developmental and practice theories and models most relevant to the phases of generalist practice. Faculty chose theoretical course content that integrated with the generalist practice skills, including ecological systems, attachment, trauma, identity development, psychosocial development, family systems, aging, social learning, and crisis. This change required collaboration between faculty teaching the generalist curriculum and those teaching the advanced clinical curriculum.

In addition, faculty revised courses to enhance attention to racial and social justice. As an example, the DSM class (required for all clinical students) added the following course objective: “Analyze the impact of race, ethnicity, national origin, age, gender, sexual orientation, ability, socioeconomic status, class, and religion/spirituality on the expression and management of health and mental health issues among client populations.” New weekly content and assignment prompts are scaffolded to support this learning goal.

New Courses

Practicum partner feedback informed the development of several new courses. Given that both clinical and macro practicum partners expect students to graduate with knowledge or skills related to political and legislative advocacy, faculty developed a new community-engaged legislative advocacy elective course that occurs during the state legislative session. With the redesigned research sequence, faculty have developed several new research courses, including Applied Program Evaluation for Social Work and Arts-Based Research Methods.

Areas That Were Not Changed

While input from practicum partners was critical to the curriculum renewal process, the faculty brought their own expertise to bear in discerning how best to fulfill the program’s mission, meet the needs of students, and serve the practice needs of our communities. In some cases, the faculty opted to retain content that exceeded most practicum partners’ expectations for MSW graduates. For example, the research preparation for MSW students, while altered, still surpasses what most practicum instructors expect. In addition, the faculty has retained generalist content related to community practice (such as popular education, community assessments, and community organizing) despite this not being an expectation of most practicum instructors. This reflects the program’s priority to prepare all students, regardless of concentration, with foundational skills for working with communities and organizations, as well as with individuals and families.

This case study demonstrates one approach to engaging practicum partners in curriculum renewal. Practicum partners proved to be a meaningful source of information about our curriculum’s strengths, what knowledge and skills are most relevant to their workforce needs, and areas where the curriculum was misaligned with the expectations of practitioners. Our partners offered insight into both what students should learn in their graduate training, and when in the program that learning was most important. These findings directly informed revisions to the generalist curriculum, research preparation, and advanced concentrations.

This approach to curriculum renewal was not without limitations. We recognize that the survey response rate (32%) could impact the generalizability of our findings to a larger population of practicum instructors. Further, while we emphasized reciprocity with the professional practice community in our process, they are not the only stakeholder group that could or should inform our curriculum. Our process offered few opportunities for student input, and did not seek any input from communities served by social workers, either through direct data collection or analysis of existing needs assessments. Given social work’s ethical commitment to self-determination for individuals and communities, a more robust community-engaged process would have us also ask questions such as “What knowledge and skills do social work students expect to graduate with?” and “What knowledge and skills do those interfacing with and being served by social workers expect practitioners to have?” Given the limitations in our process, we suggest this case study might serve as an example, rather than an exemplar, of community-engaged curriculum development.

While the U.S. accrediting body now requires that curriculum be “informed by the professional practice community” (CSWE, 2022), it does not explain how to accomplish this. While CSWE could elaborate the perceived value of such engagement, we find the lack of a prescribed process appropriate, given the diversity among schools in size, geographical context, community demographics, and social service needs. Rather than follow a prescriptive process of community-engaged curriculum development, we suggest that schools of social work adopt a values-driven approach, and imagine for themselves what it would look like to center reciprocity and accountability in the curriculum renewal process. Additional case studies describing these processes could aid schools of different sizes and contexts to imagine possibilities for meaningful community engagement in curriculum development and revision, as could further research of practicum partners’ expectations of, satisfaction with, and ideas for more meaningful engagement in social work curriculum. Just as it is inappropriate for social workers to practice in a vacuum—without seeking or considering input from clients, colleagues, and community—so too is it flawed for faculty to simply teach what they want, how they want. Our responsibility to our communities warrants integrating our curiosity and care about their needs, experiences, and expectations alongside our knowledge of existing and emerging social work scholarship and best practices in social work education. Ultimately, engaging practicum partners in curriculum development may help us better understand the needs of our community, prepare practitioners who can better meet those needs, and strengthen relationships with those we consider our primary partners in graduate social work education.

References

Council on Social Work Education. (2025). 2022 EPAS interpretation guide for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs, version 5.20.2025. https://www.cswe.org/getmedia/78815b36-1a82-47de-be69-fe3191c08762/2022-EPAS-Interpretation-Guide.pdf

Cronin, T., Dunn, K., & Lemus, C. (2021). Toward a community-informed social work curriculum: Responses from local social workers. Journal of Sociology and Social Work, 9(1), 60–72. https://jssw.thebrpi.org/journals/jssw/Vol_9_No_1_June_2021/8.pdf

Dalton, B., & Wright, L. (1999). Using community input for the curriculum review process. Journal of Social Work Education, 35(2), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.1999.10778966

Gallup, D., Henwood, B. F., Devaney, E., Samario, D., & Giang, J. (2023). Shifting social worker attitudes toward homelessness: An MSW training program evaluation. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 32(2), 324–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2022.2061238

Garcia, M. L., Mizrahi, T., & Bayne-Smith, M. (2010). Education for interdisciplinary community collaboration and development: The components of a core curriculum by community practitioners. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 30(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841231003705255

Greenwood, M., & Palmantier, M. (2003). Honoring community: Development of a First Nations stream in social work. Native Social Work Journal, 5, 225–242. https://tinyurl.com/2u8rxj5x

Haight, W., Waubanascum, C., Glesener, D., Day, P., Bussey, B., & Nichols, K. (2019). The Center for Regional and Tribal Child Welfare Studies: Reducing disparities through indigenous social work education. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.045

Iverson, S., & James, J. (Eds.). (2014). Feminist community engagement: Achieving praxis. Springer.

Lewis, L. A., Kusmaul, N., Elze, D., & Butler, L. (2016). The role of field education in a university–community partnership aimed at curriculum transformation. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(2), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1151274

McCaslin, R., & Barnstable, C. L. (2008). Increasing geriatric social work content through university/community partnerships. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 29(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960802074214

Mehrotra, G. R., Tecle, A. S., Ha, A. T., Ghneim, S., & Gringeri, C. (2018). Challenges to bridging field and classroom instruction: Exploring field instructors’ perspectives on macro practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(1), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1404522

Morris, R., Lin, N., & Bratiotis, C. (2024). “Oh, you learn it all in the field”: Stakeholder perspectives on knowledge and skills development of MSW students. Social Work Education, 43(6), 1635–1649. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2023.2208153

National Association of Social Workers. (2021). NASW code of ethics. https://tinyurl.com/2uay7az4

Pelech, W. J., Barlow, C., Badry, D. E., & Elliot, G. (2009). Challenging traditions: The field education experiences of students in workplace practica. Social Work Education, 28(7), 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470802492031

Reisch, M. (2013). Social work education and the neo-liberal challenge: The US response to increasing global inequality. Social Work Education, 32(6), 715–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2013.809200

Sheridan, M. P., & Jacobi, T. (2014). Critical feminist practice and campus-community partnerships: A review essay. Feminist Teacher, 24(1-2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.5406/femteacher.24.1-2.0138

Simons, H. (2014). Case study research: In-depth understanding in context. In P. Leavy (Ed.) The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (pp. 455–470). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811755.013.005

Sousa, C. A., Yutzy, L., Campbell, M., Cook, C., & Slates, S. (2020). Understanding the curricular needs and practice contexts of macro social work: A community-based process. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 533–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656686

Thurber, A., & Halverson, S. (2021). Engaging field and faculty to inform the MSW curriculum. Portland State University. https://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/44038

Twill, S. E., Elpers, K., & Lay, K. (2011). Achieving HBSE competencies through service-learning. Advances in Social Work, 12(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.18060/1174

Wu, M.-J., Zhao, K., & Fils-Aime, F. (2022). Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 7, 100206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206