Abstract

Distance education is one proposed solution to workforce shortages in social work. Ensuring appropriate field placements, and supporting students within those placements, are challenges for programs. More research is needed to explore distance learning in social work education for rural states with large Indigenous populations. To address this gap, we conducted semistructured qualitative interviews with students, practicum staff, and faculty from community and Tribal colleges partnered with a large university to provide distance BSW education. A qualitative description approach and content analysis were used to interpret findings from 15 semistructured interviews. Our findings highlight several themes: (a) experiences identifying a practicum and onboarding; (b) the value of practicum work experiences; and (c) suggestions for improvements. When thoughtfully conducted, distance social work field education can help build a community-based workforce in rural and Indigenous settings.

Distance education increasingly has been proposed to address critical gaps in the social work workforce (Baker & Jenney, 2023; Menzies, 2015). A diverse set of professions, including nursing, human services, and public health, have built distance programs to address workforce development needs in these fields, including pipeline programs focused on students from low-income and underrepresented minority backgrounds (Simon et al., 2019; Webb & Spear, 2018). Across doctoral, master’s (MSW), and bachelor’s (BSW) levels, there has been a proliferation of distance options in social work (Online MSW programs, 2023). As of this writing, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), the main accreditation body for schools of social work, has accredited 91 online BSW programs. All but nine of the 91 distance BSW programs were accredited in 2018 or later, so their development is a relatively recent phenomenon, and evaluation of distance programs is still in the early stages (Council on Social Work Education, 2022). This study explores student field experiences in a distance-learning BSW program designed to address social work workforce shortages in rural and Indigenous communities. Though distance-learning programs have become more widely available, few strategically involve Tribal and rural communities in their development and implementation (DeMattos, 2019; Heitkamp et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2013). The results of this study contribute valuable knowledge to inform the development of social work distance learning for rural and underresourced communities.

Barriers to student success in distance programs include a lack of connection to other students; social, technological, and motivational issues; inconsistent written policies, guidelines, and technology; and lack of support for faculty and students (Bawa, 2016; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006). Additional challenges described by BSW students and field staff include challenges in providing adequate field education opportunities and a need for strong relationships between students and faculty (Longoria & de Lourdes Martinez-Aviles, 2014). A primary concern about using online platforms for social work education is that students may not develop the interpersonal skills needed for the profession without in-person interactions. However, innovations such as computer simulations and virtual reality are being used increasingly to teach direct practice skills, providing students with opportunities to practice in a realistic yet low-risk environment (Baker & Jenney, 2023; Huttar & BrintzenhofeSzoc, 2020). Increasing pedagogical attention has focused also on facilitating community in online educational contexts (Smith, 2015). For example, consistent feedback from faculty and trust in faculty has been shown to be helpful in providing this connection (McCarthy et al., 2022).

Despite these challenges, distance education has proven valuable for expanding access to education for nontraditional students. These students include those who are over the age of 24, working full-time, attending school part-time, have children or caregiving responsibilities, are first-generation students, or are returning to college (Afrouz & Crisp, 2021; Engle & Tinto, 2008; MacDonald, 2018). For example, a recent survey of MSW graduates indicated that students who graduated from online programs tend to be older, work full-time, or have prior social work experience (Richwine et al., 2022). These data suggest online programs may help diversify the social work workforce by reaching students for whom attending courses in person is not possible. The survey data also demonstrated that graduates from online MSW programs were more likely to return to their full-time positions after achieving their degree, and were twice as likely to work in rural communities, indicating these students may be more likely to bring their skills and education back to their community (Richwine et al., 2022).

Bolstering the social work workforce in rural areas through educational opportunities is especially needed in states such as Montana, which is one of the least populated and least urban states nationally (United States Census Bureau, 2022). The need for social workers in Montana is driven by high levels of poverty, substance use, health disparities, and rates of suicide (Chinni, 2020; Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services [DPHHS], 2025; Rural Health Information Hub, 2022; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017). These issues are exacerbated by a lack of providers throughout the state, with all but five counties being designated as mental healthcare shortage areas (Montana DPHHS, 2025). Despite the need for social workers in Montana, no studies have specifically explored social work education in Montana, and few studies explore this topic in general in rural contexts (Wright & Harmon, 2019).

Our BSW distance education program is unique insofar as it has been developed through partnerships with Tribal and community colleges. Beginning in 2010, the program described in this article was developed as a partnership between five Tribal and four community colleges throughout the state of Montana (Reese et al., 2024). Although the option of moving to the urban area where the university is located to pursue a BSW or MSW degree existed, faculty from the school of social work and Tribal and community colleges identified that unwillingness and inability to leave their communities was an obstacle that kept many students from enrolling in the school of social work.

In this program, students complete their first two years of schooling through their Tribal or community college, then apply to, and if accepted, join the University of Montana BSW program, where they complete their final two years of education online. Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) are not only responsive to the occupational needs of Native American students but also to the economic growth of the communities where those students live and work (Bordelon & Atkinson, 2020). Therefore, Native American students are more likely to succeed if they begin their first two years at a TCU and then transfer to an online or hybrid program at a mainstream university. Distance education offers the option to stay in their communities or commute more easily while they pursue their studies.

Few examples exist of these types of partnerships in the social work field. Similar programs include the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, which has adapted its program to be a hybrid online program, emphasizing the need for careful consideration of the needs of Indigenous students; the University of North Dakota’s BSW distance learning program; and a collaborative program at the University of California (DeMattos, 2019; Heitkamp et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2013). These programs have shown that recruiting and retaining individuals from Indigenous and rural communities in social work may enhance cultural relevancy in practice and education. They establish a pathway to licensure, offering predegree advising, BSW education, and an MSW degree, which is crucial for strengthening the mental health workforce (Heitkamp et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2013).The research described in this article highlights another program focused on building community-based partnerships in social work.

Purpose

The purpose of this research was to identify key strengths and areas of growth for the field education components of a distance BSW program partnered with Tribal and community colleges. As the program continues to educate social workers in our state and potentially expands, we sought to explore what has worked in the program and what may need to be adapted or changed to ensure the program meets the needs of students to ensure their success. This research contributes to needed scholarship focused on social work distance-learning education in rural and Indigenous communities. In this article, we specifically focus on the field education experiences of students, faculty, and staff.

Methods

Field Placement Program

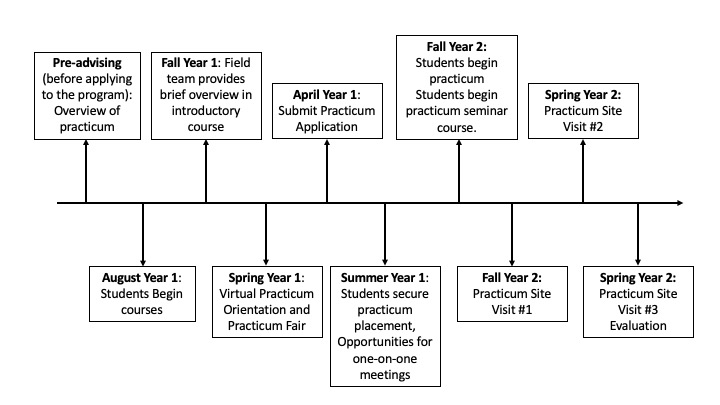

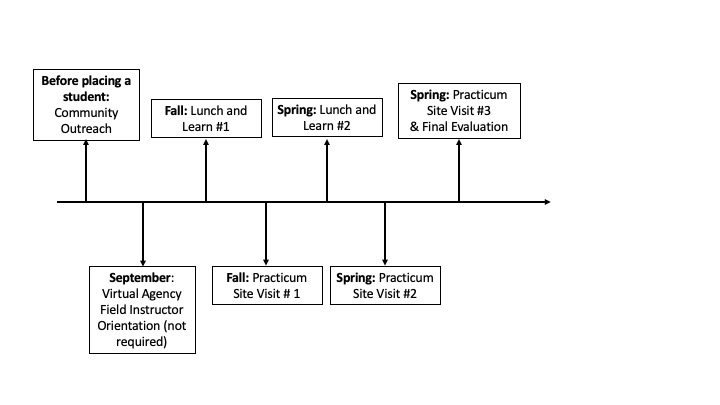

Field placements are a student-driven process in the distance-learning BSW program featured in this manuscript. Students consider different agencies where they would like to complete their practicum, and then reach out to those sites to secure a placement. The field team provides support and guidance throughout this process (see Figures 1 and 2 for detailed timelines). This process mimics professional outreach and the application and interview process that students will encounter as social workers, and is viewed as an opportunity to develop professional and communication skills. The process also allows students to create a practicum experience that fits their interests and needs. It is important to note that field placements in the distance-education program were traditionally offered either online or in-person, depending on the site. However, this study was conducted in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. To adapt, our program, which had previously included required in-person meetings, moved completely to virtual. The field education team was responding to the needs of students, the needs of partnering agencies, rapidly changing policies, and workforce challenges and staffing transitions resulting from the pandemic. For a more detailed description of the development of this program, please see Reese et al. (2024).

Figure 1

Distance-Learning BSW Program: Field Placement Timeline

Figure 2

Distance-Learning BSW Program: Field Placement Supports

The responsive interviewing model informed the semistructured interview protocol, allowing for a natural flow and flexible interview environment that encouraged follow-up questions (Rubin & Rubin, 2012). Informed consent and consent to record was received from each participant prior to the interviews.

Data Collection and Sampling

Study participants were sampled from a pool of students, faculty, and field instructors engaged in the program when the study was conducted (2022). A variety of recruitment methods were used to reach student, faculty, and staff participants. All students enrolled in the distance-learning program during the study were sent emails inviting them to participate. Those interested were encouraged to contact one of the study authors to schedule an interview. A total of 20 students completed the survey, and eight students volunteered for interviews. Additionally, four faculty members and three field support staff participated in interviews. All faculty from Tribal and community colleges who had supported at least two cohorts of students were also invited to participate via email. We invited all agency field instructors currently supervising students to participate in the study through email. To participate, individuals were encouraged to reach out to the study PI. Previous partnerships with individuals from partnering colleges also helped spread the word about the project to eligible participants.

Between 2019 and 2024, 161 students enrolled in the distance BSW program. Of those students, 136 (84%) identified as female. Students reported the following racial identities: White (58%; n = 93), American Indian/Native American (34%, n = 54), Asian (n = 2), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n = 1), and no response (1%, n = 11). Fifty-eight percent of students (n = 93) identified as first-generation students; 14 % (n = 23) reported having a disability; and 85% (n = 137) received a Pell grant during their time in the program.

All interviews were conducted and recorded using Zoom and occurred between March and May 2022. Participants signed release forms and were given informed consent and information about the study before beginning the recording. This study was determined to be IRB exempt by the University of Montana IRB. The responsive interviewing model informed the semistructured interview protocol (Rubin & Rubin, 2012). This model encourages a natural flow of conversation between interviewer and interviewee and ample use of follow-up questions. Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service and checked by the PI for accuracy. Each interview lasted approximately 15 to 44 minutes, with an overall average length of 32 minutes. Interviewees were mailed a gift card totaling $30 as a thank-you for their participation.

Data Analysis

A qualitative description methodology was used for this study. This approach is a pragmatic, naturalistic method of qualitative research that emphasizes a low-level interpretation of interviewee quotes, in contrast to more abstract or highly interpretative methods (Sandelowski, 2000). The goal in qualitative description is to produce descriptive findings and not to produce theory (Sullivan-Boylai et al., 2005). Findings are presented using everyday language, meant to be directly translatable to interventions (Sandelowski, 2000; Sullivan-Boylai et al., 2005).

Interview transcripts were analyzed in NVivo by a team of two researchers, who first read the interviews several times to immerse themselves in the data and created a preliminary list of themes. These themes were then used to code the interview transcripts. Subthemes were added to the coding scheme as coding progressed, resulting in a final hierarchical coding scheme (Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2005). For example, the initial code “impact of program on local community” might be further refined to “increased number of social workers” and “developed new relationships with local agencies.” All interviews were coded by two coders, and Cohen’s kappa coefficient was between 0.82 and 0.99, indicating high interrater agreement (Burla et al., 2008; McHugh, 2012). ID numbers were assigned to participants, and it is noted throughout the results whether participants were field staff, students, or faculty members. Field staff are employed by the community organization where students complete their practicum. They provide day-to-day supervision and evaluate students’ progress towards gaining gaining mastery of social work competencies.

Rigor and Ethical Concerns

This study was an informal evaluation of a current distance-learning BSW program. The program arose as a result of strong relationships with Tribal communities throughout the state, facilitated by the program director and other faculty members. In line with the program’s community-driven approach, members from the program itself were invited and included to participate in this research. To combat potential bias due to the involvement of program staff and faculty, social work researchers from outside the program conducted the interviews, analyzed results, and helped write manuscripts. The participants’ identities were blinded before the results were shared with members of the program who were on the research team.

All members of the research team identify as non-Indigenous. Our position as non-Indigenous researchers necessitated particular sensitivity and reflection, and a research approach that was culturally congruent for research with Indigenous groups. We engaged in this reflection process before the research began and throughout the project. In reflecting on our position, we strove to go beyond simply focusing on biographies to closely examine the structural economic, social, and political forces involved in this project (Brown & Strega, 2015).

Results

Students, faculty advisors, and field staff all provided their perspectives on the distance BSW program, including areas of strengths and areas where the program could be improved. Some of the key themes identified and discussed in more depth below include: (a) experiences identifying a practicum and onboarding; (b) the value of practicum work experiences; and (c) suggestions for improvements.

“I still just don’t know really what my options are.”

Experiences Identifying a Practicum and Onboarding

Students and field staff (FS) both expressed a need for clearer communication and increased information surrounding practicum identification and onboarding. Several students expressed that there was an expectation that they were solely responsible for identifying a practicum and received little guidance or support. One student described it this way:

“Okay, go find your practicum.” I’m like, “What? What do you mean?” I don’t know. I was thinking it would be a little more, “Here’s your choices. Here’s some options.” They know they’re willing to take, and they just keep talking about like, “It’s a job.” Well, no, really? It’s not, it’s not a job. I have to have this, I’m working for free. (S5)

This student noted a dissonance between how practicums were considered work but not compensated accordingly. Because a practicum was a required aspect of their learning, they felt they needed more support in securing a site. Field supervisors also noted that students seemed unclear on practicum requirements and struggled to identify a practicum in time to start the program. In describing students’ experiences beginning the practicum process, one field supervisor stated,

[It] seems to consistently be rocky, and the students don’t know what their requirements are, and they don’t know what their supervision requirements are …. This is something that is our lapse in structure, but we don’t have an application that we use. Now we will, and it will ask those very clear questions, how many hours per week? What’s the start date? What’s the end date? … It is not uncommon for us to hear from students the first week in August, and they are frantic, and they still don’t know what it is they need. I don’t know where the breakdown is happening there for them, but it does make it difficult to get started. (FS1)

These quotes suggest that increased efforts are needed to connect students with support regarding practicum identification and onboarding.

One student described having difficulty finding a practicum site where they were located: “I’m your outlier, so I’m not from [areas where there are a lot of existing placements]. They [other students] all had their agencies already in the system.” (S3) This participant’s experience suggests that established practicum sites exist in some regions or areas in the state but not as robustly in others. Another student described identifying a practicum site by referencing their prior experiences and family connections:

I was like, “What if I did school-based social work?” Because there’s already social workers there that I know of from the time of just like meeting them because my family works in the school. I was like, “What if I just do this instead?” I had to get that approved, which was stressful, but it got done. I’m pretty thankful for it. (S6)

Identifying opportunities for new practicum sites in one’s community is a way students can locate learning opportunities of interest in the program, though this process was described as challenging. Other challenges in practicum onboarding included long waits for background checks:

I was applying for a job with the Tribe to get into social services. Then I also had to do a thorough background check. I’m a foster parent so I already had a background check but the Tribe had to do an in-depth background check. They even check your credit … so that took a really long time. (S1)

Background checks are necessary for some sites, and being prepared early to undergo the background check process could benefit students.

“I feel like I’ve learned more than the average bear.”

The Value of Practicum Work Experiences

Students reported learning a great deal from practicum experiences and feeling valued by the organizations where they were placed. For one student, their practicum provided them with an opportunity to try out an area of interest:

It is a difficult court research experience. I like laws. I wanted to be an attorney at one point, but now that I see what my boss has to go through, I’m like, I’ll just stick with my Master of Social Work. You still have to read policy procedures and laws and whatnot, but not on the level that they do. It’s so complex …. It’s a great experience learning about domestic abuse advocacy on a federal level, macro, mezzo, and micro. (S2)

Through their practicum, this student learned what it would be like to work in law. This experience confirmed that social work was the right fit for them.

Other students also described their practicum as a positive learning experience. One student reported learning a wide variety of skills: “I feel like I’ve learned more than the average bear to be honest. I learned about grant writing, learned about reporting, learned about how funding operates on a federal level. I could go on and on about it.” (S3)

This field supervisor also noticed that they sometimes needed to adjust their expectations depending on the academic and experience levels of different students:

It was definitely a little bit of a learning curve of resetting some expectations and what are the bachelor’s level expectations versus what are the master’s level expectations? How do I give a good internship within these parameters? I was also a little bit spoiled. I have a phenomenal intern who probably does more than she should be capable of at this point in her educational journey. She has a really extensive mental health background and has been in the field as a direct care level staff and as well as a behavior intervention specialist, and so I was definitely a little bit spoiled. (FS2)

Another field supervisor agreed that the connection between the curriculum and the work is vital:

Going back to some of the other things that make it successful … one thing I tried to reinforce with [the student] was thinking about how her course requirements would overlap with what she was doing for us as well and trying to help her to connect those things so that if she wanted to take a bigger bite out of a topic, she had more time to do it as opposed to, check, check, check, boxes. (FS3)

They found insight into field supervision by referring back to their own experience as a student: “There’s no way I would have gotten as much out of my practicum if I couldn’t very quickly apply it to what I was learning in the classroom.” (FS3)

Lastly, one student mentioned how emotionally overwhelming a practicum could be and felt it would be helpful for everyone, students and staff, to be able to talk about what happens on the job and support each other through it:

The place where I was placed, it’s the commercial for Las Vegas, what you hear stays here, what you see here stays here. It’s an indefensible position because you can’t talk about anything. You can’t defend yourself, you can’t share any information to get rid of the burden of what you see and hear and read. I wasn’t prepared for that …. They didn’t have it either. It wasn’t ever on the list of priorities, even for the social workers that are there. They need that because they have new workers there that really could use the self-care, the sharing of the unburdening, things that you’ve collected on your back during the day. (S1)

This quote suggests a need for more spaces for students to share their practicum experiences with others.

Another field supervisor discussed the importance of prompt and thorough communication, especially for logistical matters like scheduling visits:

I think the only feedback I have is sometimes I didn’t always hear when things were due unless it was from my intern and a lot of the scheduling then for site visits and things like that went through her as well, which is fine. It’s just a different way of doing things than some other places. It didn’t negatively affect anything. Sometimes it was just hard scheduling three people’s times through my intern. (FS2)

Students also mentioned other positive aspects of the practicum experience. For example, one student expressed appreciation for the tech support:

Once I got the hang of it, it was pretty easy, but the only part of the practicum I thought was challenging was making sure I got to get the stuff done on Sonia [a software for tracking practicum hours, communication, and paperwork] on time. Everybody was really helpful. If you emailed them, they email you right back and walk you through it. (S2)

Another student felt that it was helpful to have the practicum organized as it was in the program: “The foundations are really good when it comes to, just the way that the practicum is split up.” (S6)

Lastly, one student described the importance of providing education to students across the state: “I love the idea that we’re all over the state, I think that’s a great—I do think it’s such a field that needs people.” (S8)

“I see where it could be educationally beneficial as well to tie that in.”

Suggestions for Improvements

One field supervisor suggested that students should be able to use their existing job as a practicum site, as it would expand their understanding of the curriculum as well as the work. Encouraging work-based placements was also suggested as a potential avenue for students struggling to identify a practicum site:

I don’t know what the rules are, but not being able to use their existing paid work as their practicum site, I would identify as a barrier. I think part of it was if they were at their job, then their practicum responsibilities needed to be different from their prior responsibilities. One question I would ask is, why is that? Both times that we had practicum students who were working elsewhere, we got way less of them. Just that makes sense, and I think they also lost the opportunity to look at their employment through their educational lens. I think that, especially for single working moms which two out of three have been really difficult to add the practicum expectations on top of them being a full-time student and a part-time to full-time worker. I see where it could be educationally beneficial as well to tie that in. (FS1)

Though work-based placements are allowed in the program, this participant’s quote suggests that this is not widely known and that there still exist barriers to utilizing employment as a practicum site.

This field supervisor also suggested that the learning agreement required by the program could be more expansive and creative, adapting to the lived experience of the students:

One of them [suggestions] is sometimes that the learning agreement feels so detailed that it becomes restrictive, and that you’re just like, “Let’s just get through this. Let’s just go through the motions and say yes to what we need to say yes to, as opposed to inviting creativity, inviting true thought about what that student’s own personal goals are.” (FS1)

This participant believes that having a more open-ended learning agreement would give students more opportunities to set their own goals.

Students’ quotes described the difficulty of identifying a practicum site and a need to bolster resources. One student reported attending a panel discussion with previous students, as part of the program’s efforts to share information about potential sites. They stated, “I can’t say it [the panel] was helpful. I think that would’ve helped a lot if people showed up. There were very, very few people there.” (S7) Unfortunately, based on their quote, this panel was not well attended. Another participant stated that it would be helpful if “somebody from the university, actually compiled some kind of list [of practicum sites].” (S8) Notably, a list of available sites does exist, yet this student’s unawareness of these sites perhaps indicates a need to share this information more widely. Additionally, orientation was noted as an opportunity to educate students about their practicum options. In describing what this might look like, one student stated,

Really just breaking down, like, this is what you’re going to utilize. This is how it may look, this is how you could prepare for it [the practicum]. If you don’t know how to do these, we can break down other options for you. (S6)

Students indicated that they wanted more detailed information about practicum sites and processes.

Field supervisors spoke about the importance of experiencing both online and in-person learning. However, they also noted that so much of the students’ lives are online that there is balance in working in-person as well: “I would imagine that there’s a lot of students that would love to have an in-person placement, just to balance out the virtual.” (FS3)

Like the students, field instructors also noticed the challenges that arise when students are choosing and preparing for a practicum. Their own past experiences with practicums were valuable in their roles as mentors. For example, one FS’s experience with distance learning helped them to provide quality supervision to distance learners: “I would not have felt as comfortable doing a remote supervision had I not experienced that previously at practicum.” (FS3) This FS also noted the added benefit of having multiple mentors—at least one inside the field placement organization and one from the academic institution:

I know it’s an extra cost, sometimes to the department, but if you have an outside supervisor as well as your site supervisor, that was one thing that in contrast to the other members of my cohort, those of us that had both, you had someone who was prodding you on power structure, where you have a person that’s not what their interest lies. They’re not there hiding or anything, it’s literally just trying to teach you enough to do the work. Whereas you can have really critical lenses with that outside supervisor, where you get a little bit tougher questions that either aren’t really that pertinent to the work that you’re working on in the practicum placement or it’s just not safe to ask. I didn’t have a lot of problems in mine, but I know of some other placements that could have really helped some folks learn how to navigate difficult conversations. There was help if folks asked for it, but not full-throated endorsement [for having both an internal and external mentor]. (FS3)

This participant describes how internal and external mentors can complement each other’s perspectives, each providing insight that may not be the central focus of the other’s perspective, particularly when it comes to the power structure of an organization. Having multiple mentors may aid in students learning and provide more opportunity for reflection and support.

Discussion

Participants provided valuable feedback on their distance BSW program field experiences, such as emphasizing the importance of receiving information about practicum sites, finding or creating a “good fit” placement, and having a clear connection between the academic material and the work. Distance education is becoming an increasingly common solution to social work workforce gaps, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, and requires innovative approaches to field placement (Arundel et al., 2022; Lomas et al., 2023). The findings of this research demonstrate key strengths, lessons learned, and implications for future programs and educators.

The lessons learned from these interviews suggest more resources are needed to help students identify a practicum site that meets their learning goals. Though creating one’s practicum within one’s community is possible and valuable, not all students may have the time, energy, or wherewithal to complete the logistical requirements to make this happen. Additional support for locating or developing practicum sites for students in remote and rural areas could be beneficial. While employment-based practicum experiences are supported in the program, field instructors and students advocated for methods of facilitating these placements for students who are already working or have connections to an organization. Finally, though a list of placements is available, these findings illustrate that not all students may be aware of this list and that it may not have up-to-date contact information.

Students also described program strengths, such as feeling valued by their placement and gaining a wide variety of experiences. They noted that it was beneficial when the program reached out to students across the state. However, students also reported that more opportunities to process and discuss practicum experiences would be valuable. Field instructors echoed this perspective and stated they benefited from the work of students who were particularly skilled and proactive. Field staff also advocated for methods of closely connecting practicum experiences to in-class learning and opportunities for students to have mentors within and outside of the practicum setting.

Much of these research results have been described elsewhere as common issues in social work programs. However, in the context of this program’s rurality and partnership with Tribal communities, these results have unique meaning. For example, the importance of peer support and strong supervision in social work practicum placements for student learning is well-known (Ben‐Porat et al., 2019; Bogo et al., 2022). Current literature suggests that social work students may exhibit higher-than-average adverse childhood experiences scores and may have come to the social work profession due to personal experiences, putting them at higher risk for experiencing secondary trauma (Steen et al., 2021; Thomas, 2016). Peer support and supervision are needed to mitigate this trauma. For students of this distance-learning program, many of whom are Native American and first-generation students, supervision and support during field education experiences may be especially important for building and contributing to resiliency and well-being.

These findings also elucidate the strengths of nontraditional students upon entering the social work field. Participants described students as having a high level of competency and taking on additional challenges in field placements. Students’ efforts to identify new practicum placements or create placements within their workplace were also evidence of competency. Nonetheless, this resiliency does not preclude the need for ongoing support.

Difficulty locating a practicum site, particularly in certain areas of the state, may indicate a dearth of social support services in rural areas. The vast majority of counties in the state are considered Mental Health Provider Shortage Areas (Montana DPHHS, 2022). Considering that a major goal of the program is to bolster the social work workforce, efforts to explore the current social work infrastructure to identify opportunities for students are needed. Recruiting alumni as field staff in communities where students are located could help build this infrastructure, and offering field education placements closer to home also benefits communities, particularly rural and Indigenous communities (Bordelon & Atkinson, 2020).

Many of these findings have already been incorporated into improvements to our program (see Table 1), including (a) requiring attendance at a hybrid orientation six months before starting practicum; (b) adding a more detailed assessment of needs as a part of the practicum application; (c) conducting in-person visits across the state; (d) creating and sustaining community liaison positions, and (e) reestablishing a mentor program where students are matched with faculty members who share their practice or research interests. One challenge we face is balancing the flexibility of distance education with providing opportunities for in-person meetings. Findings appearing in adjacent manuscripts highlight students’ desire for additional opportunities for in-person connection (Carlson et al., 2024).

Table 1

Changes Made to the Practicum Process as a Result of Lessons Learned from the Covid-19 Pandemic and Student Feedback

| Previous process | Current process |

| Virtual practicum orientation was not required | Hybrid practicum orientation is required |

| Required a practicum application | Added an assessment to the required practicum application (includes criminal history, accommodations, etc. needed) |

| Met virtually due to Covid-19 policies | Resumed in-person meetings both at the larger university and annual visits to community and Tribal colleges |

| No liaisons | Hired liaisons for select Tribal communities |

| No mentor program | Re-established mentor program |

| More stringent policies from CSWE surrounding employment-based practicums | More relaxed policies from CSWE surrounding employment-based practicum |

We want to support students’ need for flexibility and their desire for increased in-person events. As such, we have also decided to require attendance at a hybrid orientation to better prepare students for the practicum experience. We have returned to arranging for administration and faculty annual and biannual in-person visits to partnering colleges. We also plan to advocate for more resources to be able to engage in outreach to possible practicum sites across our state, support travel across the state for program staff and faculty as well as students, and support community liaisons in select communities. We are also considering the best ways to engage and support field staff. We offer an orientation, continuing education opportunities, and site visits, but do not require field staff to engage in these offerings.

Over this period, and in response to the pandemic and student advocacy, CSWE relaxed requirements related to employment-based practicums. Though we always allowed employment-based practicums, these policy changes allowed us to better support employment-based practicums. Finally, we have noticed an increased need for mental health support throughout the pandemic, which has, in some cases, impacted students’ practicum experiences. As a distance program, our university does not provide ongoing mental health support to our students. This is a need we continuously advocate for as a program. Our university has invested in a well-being support coach program, staffed by MSW students who can provide peer support to distance-education students via telehealth. This has proven to be a valuable resource for students, faculty, and staff.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, we have learned valuable lessons about field education. Due to restrictions, we pulled back from requiring in-person opportunities, and we have seen the impact. Ultimately, we have seen students negotiating growing demands in their personal and professional lives. Many of our students are single parents, working full-time, and/or living with mental health, social, and financial stressors. Another challenge we face is being inclusive with regard to who is accepted into our programs, while also ensuring students are ready to engage in practicum and be successful. We hope to continue supporting students as a program, and through these efforts address workforce needs in our state.

Limitations and Future Research

Our findings highlight the importance of carefully tailoring educational programs to meet community and student needs. However, due to a low sample size and the specificity of this research, these results are difficult to generalize to other programs and contexts. Further research is needed to ensure that future educational programs are developed specifically for the unique needs of the community and students.

There were efforts to minimize bias as a result of program faculty involvement in this study, including anonymizing data prior to analysis and having researchers from outside the program conduct interviews. These researchers include a master’s student in public health and two MSW faculty members, who strove to analyze and present the data clearly and authentically. Nonetheless, program faculty involvement could be a potential conflict of interest. These interviews were also cross-sectional. Although attempts were made to interview students at both the beginning and at the end of the program, future research would benefit from interviewing the same students over time to explore potential changes in their attitudes and perspectives of the program.

In addition, as with most research, there is also the potential for selection bias, since not all students in the program were interviewed, and we were unable to interview all faculty and practicum staff affiliated with the program. We hope that, by interviewing students from a variety of community and Tribal colleges and students who had both positive and negative experiences in the program, we are able to reflect an honest portrayal of the strengths and weaknesses of this program.

Conclusion

This study explored the experiences of students, faculty, and field supervisors in an institutional partnership program where students learn in their home communities for the first two years and then transition to a university to complete their BSW. Findings underscore the importance of relationship, communication, and support. Given the workforce shortages in rural and Indigenous communities in particular, it is vital to build a strong body of knowledge around best practices in distance social work education programs.

References

Afrouz, R., & Crisp, B. R. (2021). Online education in social work, effectiveness, benefits, and challenges: A scoping review. Australian Social Work, 74(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2020.1808030

Arundel, M. K., Morrison, S., Mantulak, A., & Csiernik, R. (2022). Social work field practicum instruction during COVID-19: Facilitation of the remote learning plan. Field Educator, 12(1). https://tinyurl.com/4myfzpvn

Baker, E., & Jenney, A. (2023). Virtual simulations to train social workers for competency-based learning: A scoping review. Journal of Social Work Education, 59(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2022.2039819

Bawa, P. (2016). Retention in online courses: Exploring issues and solutions—A literature review. SAGE Open, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015621777

Ben‐Porat, A., Gottlieb, S., Refaeli, T., Shemesh, S., & Reuven Even Zahav, R. (2019). Vicarious growth among social work students: What makes the difference? Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(2), 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12900

Bogo, M., Sewell, K. M., Mohamud, F., & Kourgiantakis, T. (2022). Social work field instruction: A scoping review. Social Work Education, 41(4), 391–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1842868

Bordelon, T. D., & Atkinson, A. (2020). A pathway for Native American students to access a mainstream university for social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1642272

Brown, L. A., & Strega, S. (Eds.). (2015). Research as resistance: revisiting critical, indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches (2nd ed.). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Burla, L., Knierim, B., Barth, J., Liewald, K., Duetz, M., & Abel, T. (2008). From text to codings: Intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nursing Research, 57(2), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nnr.0000313482.33917.7d

Carlson, T., Liddell, J., Reese, S., & Cooper, D. (2024). “I got to sit at the table”: The impact of distance social work education in rural and tribal communities in Montana. Chronicle of Rural Education, 2(1). https://tinyurl.com/32sbeeex

Chinni, D. (2020). American communities experience deaths of despair at uneven rates. American Communities Project. https://tinyurl.com/54wufjbc

Council on Social Work Education. (2022). Directory. https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/directory/?

DeMattos, M. C. (2019). Native Hawaiian interdisciplinary Health Program: Decolonizing academic space, curriculum, and instruction. Intersectionalities, 7(1), 51–67. https://journals.library.mun.ca/index.php/IJ/article/view/2078

Engle, J., & Tinto, V. (2008). Moving beyond access: College success for low-income, first-generation students. The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504448.pdf

Heitkamp, T., Vermillion, L., Flanagan, K., & Nedegaard, R. (2015). Lessons learned: Outreach education in collaboration with Tribal colleges. Journal of American Indian Education, 54(2), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaie.2015.a798547

Huttar, C. M., & BrintzenhofeSzoc, K. (2020). Virtual reality and computer simulation in social work education: A systematic review. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1648221

Lomas, G., Gerstenberg, L., Kennedy, E., Fletcher, K., Ivory, N., Whitaker, L., Russ, E., Fitzroy, R., & Short, M. (2023). Experiences of social work students undertaking a remote research-based placement during a global pandemic. Social Work Education 42(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2054980

Longoria, D. A., & de Lourdes Martinez-Aviles, M. (2014). Working through challenges and solutions encountered in a social work distance education program. HETS Online Journal, 4(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.55420/2693.9193.v4.n2.188

MacDonald, K. (2018). A review of the literature: The needs of nontraditional students in postsecondary education. Strategic Enrollment Management Quarterly, 5(4), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/sem3.20115

McCarthy, K. M., Wilkerson, D., & Ashirifi, G. (2022). Student and faculty perceptions on feedback in a graduate social work distance education program. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 42(4), 392–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2022.2102103

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900052/

Menzies, K. (2015). Education at a distance: Virtual classrooms bring healthcare classes to rural areas. Rural Health Information Hub. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/rural-monitor/education-at-a-distance/

Montana Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Montana health professional shortage area (HPSA) designations. https://dphhs.mt.gov/ecfsd/primarycare/ShortageAreaDesignations

Montana Department of Health and Human Services. (2025). 2023 state health assessment. https://dphhs.mt.gov/assets/publichealth/ahealthiermontana/2023_Montana_SHA.pdf

Morris, T., Mathias, C., Swartz, R., Jones, C. A., & Klungtvet-Morano, M. (2013). The pathway program: How a collaborative, distributed learning program showed us the future of social work education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 33(4-5), 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2013.832718

Online MSW programs. (2023). https://www.onlinemswprograms.com/online-msw-programs/

Reese, S. E., Liddell, J. L., & Cooper, D. (2024). Findings from an evaluation of a distance BSW Program. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 44(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2023.2283880

Richwine, C., Erikson, C., & Salsberg, E. (2022). Does distance learning facilitate diversity and access to MSW education in rural and underserved areas? Journal of Social Work Education, 58(3), 486–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1895929

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. (2012). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Rural Health Information Hub. (2022). Rural data explorer: Health professional shortage areas. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/data-explorer?id=209

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. Simon, M. A., Taylor, S., & Tom, L. S. (2019). Leveraging digital platforms to scale health care workforce development: The career 911 massive open online course. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 13(5), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2019.0045

Smith, W. B. (2015). Relational dimensions of virtual social work education: Mentoring faculty in a web-based learning environment. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0510-5

Steen, J. T., Senreich, E., & Straussner, S. L. A. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences among licensed social workers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 102(2), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389420929618

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Suicide clusters within American Indian and Alaska Native communities. U.S. Department of Human and Health Services. https://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/gpo137879

Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Bova, C., & Harper, D. (2005). Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: The use of Qualitative Description. Nursing Outlook, 53(3), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005

Tallent-Runnels, M. K., Thomas, J. A., Lan, W. Y., Cooper, S., Ahern, T. C., Shaw, S. M., & Lieu, X. (2006). Teaching courses online: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 93–135. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076001093

Thomas, J. T. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences among MSW students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 36(3), 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2016.1182609

United States Census Bureau. (2022, July 1). U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Montana. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/MT/PST045222

Webb, A. A., & Spear, B. T. (2018). Assessing nurse capacity and workforce development in low resource settings. Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care, 3(127). https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100127

Wright, R. L., & Harmon, K. W. (2019). Challenges and recommendations for rural field education: A review of the social work literature. Field Educator, 9(2). https://tinyurl.com/578tp3x3″ target=”_blank”>https://tinyurl.com/578tp3x3