Social workers are engaged in practice that encompasses the core values of the social work profession: service, social justice, dignity and worth of the person, importance of human relationships, integrity, and competence (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2013). Social workers are on the front lines of providing service and care to those impacted by alcohol and substance misuse (Wells et al., 2013). Too often, social workers observe the devastating effects of substance misuse in individuals, their families, and the community. The NASW acknowledges substance use in its ethical guidelines and established an addictions concentration providing advocacy, training, and support for social work providers who specialize in this area (DiNitto, 2005).

Stigma, the disproportionate burden of legal consequences, and the perspective that substance misuse is a moral failing add to the complexity of treatment access and success for African Americans (Ghonasgi et al., 2024). These factors are compounded by a lack of economic divestment and poverty, which contribute to intergenerational substance misuse in African American families (Hankerson et al., 2022). Mistrust in the health care system, social services, and the justice system often deters African Americans from seeking treatment for fear of negative consequences (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMSHA], 2020).

In 2013, the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare (AASWSW), a cadre of policy, practice, research, and academic thought leaders in social work, identified “Grand Challenges for Social Work” that are salient to the profession (Grand Challenges for Social Work, n.d.) and provide a blueprint for social work action in addressing major social welfare problems in society. The Grand Challenges broadly identify individual and family well-being, a stronger social fabric, and a just society as key priorities for the social work profession (Coyle, 2020). Begun and Clapp (2015) highlighted substance misuse as a Grand Challenge for social work as it impacts multiple domains at the individual, community, and environmental levels within these key priorities. Social work is in a unique position to provide comprehensive services by addressing acute and chronic needs with clients, including co-occurring disorders and polysubstance use patterns.

Instruction about substance misuse is not a core requirement in most schools of social work, and there is a limited number of faculty with expertise in addictions (Russett & Williams, 2015). Social workers provide services to individuals impacted directly or indirectly by substance misuse; however, the percentage of social workers who receive education about addictions and training to screen, identify, and assess for substance misuse is outmatched by other professionals with specific training and preparedness (Fischer et al., 2014). An evaluation of graduate-level social work faculty perspectives on substance misuse education found that the presence of instruction in substance misuse was imperative; however, they also reported that master’s level social work students were not equipped to identify substance misuse in practice settings (Minnick, 2021). The shortfalls in the integration of substance misuse in social work education (Estreet et al., 2017; Kourgiantakis et al., 2019; Senreich et al., 2013; Wilkey et al., 2013) translate into missed opportunities for social work graduates to recognize substance misuse in practice.

Infusing substance use education and training within graduate schools of social work will increase the knowledge and capacity of students to provide counseling services and support linkage in communities experiencing the detrimental effects of substance misuse. Evidence supports the need for social work curricula to include education on substance misuse to improve the ability, knowledge, and comfort of graduate social work students in working with clients who present with substance use disorders. Putney et al. (2024) evaluated the views and perspectives of social work students on the impact of substance misuse education that was initiated in a master’s program. and found that the sample of students surveyed reported an increase in knowledge and personal awareness, and a deeper understanding of the importance of client-centeredness in the delivery of substance use care in social work. Additionally, Halmo et al. (2024) found that substance misuse education increased knowledge of intervention skills and beliefs about the effectiveness of harm reduction strategies.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have a long history of contributing to workforce diversity by educating and training students in social, behavioral, and health disciplines to serve as treatment providers in underserved communities. Given the significant role of HBCUs in preparing underrepresented graduate and professional students, challenges remain in achieving workforce diversity among substance abuse providers in social work and other behavioral health disciplines such as psychiatry and psychology (Jordan & Jegede, 2020). Barriers that contribute to the underrepresentation of African Americans in behavioral health are rooted in historic disparities, including racism and segregation, socioeconomic factors, and a scarcity of mentors and role models (Ajluni et al, 2025). African American service providers report a lack of support and resources, along with a dearth of opportunities to introduce culturally relevant training and practice to the addictions field (Hughes et al., 2022).

The purpose of this article is to discuss how infusing Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) training in agency-based education prepares HBCU social work graduate students to screen and identify substance misuse in social work practice. Each component of SBIRT is highlighted to include culturally responsive skills that master’s-level HBCU social work students are provided through instruction and application. Future implications for social work education and practice are discussed, along with recommendations.

SBIRT Background

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is a nationally recognized evidence-based approach that addresses at-risk alcohol and drug use in a variety of settings (Thoele et al., 2021). SBIRT has been adopted, promoted, and supported by federal health and human service agencies, community-based behavioral health, and social service providers. Since 2003, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) has provided support for medical professional programs to engage in SBIRT training and practice (Aldridge et al., 2017) to prepare and increase the workforce of physicians who can identify, screen, and assess for at-risk alcohol and drug use in medical settings. In 2013, SAMHSA expanded the scope of SBIRT by including support for graduate social work programs to increase knowledge and skills for the early identification of substance misuse. The SAMHSA SBIRT initiative also prepares social work students to serve with integrated and multidisciplinary service providers.

SBIRT entails several components, including universal screening for alcohol and drug use to determine the level of risk and the severity of use. Through SBIRT, Screening (S) is interwoven into services to help reduce stigma and lower the risk that individuals may underreport when providing information about current and past alcohol and drug use. Routine screening also greatly reduces the impact of stigma, which allows for a stronger therapeutic relationship (Gomez et al., 2023; Lawrence et al., 2022; Manuel et al., 2015; Senreich et al., 2013; Ting et al., 2023; Wacker et al., 2023). Brief Intervention (BI) is an SBIRT component that allows individuals to receive brief, time-limited counseling to address at-risk and harmful use of alcohol and drugs based on initial screening results. Motivational interviewing guides the brief intervention process, which helps to facilitate change for substance misuse. Referral to Treatment (RT) is offered to individuals whose screening and brief intervention results warrant the need for further counseling and treatment for alcohol and drug use. During the RT process, empathy and support are extended to individuals by the SBIRT provider, resulting in a warm handoff to treatment services. Providing empathy and support are common skills across helping professional disciplines, including social work, and are transferable across practice settings.

The Howard University School of Social Work SBIRT Training Program

The SBIRT program at Howard University was initiated in 2008 with the Howard University College of Medicine (HU-COM) through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) medical residency program for residents and fellows in multiple primary and specialty care disciplines. Recognizing the impact of substance use disorder in multiple practice settings, in 2015 the graduate social work program was added to the medical residency SBIRT training activities. Extending SBIRT within the Howard University School of Social Work (HUSSW) through the support of the HU-COM expanded the knowledge and skills of graduate social work students in preparation to practice with underserved populations and communities, providing culturally appropriate services for substance misuse.

HUSSW’s Office of Agency-Based Education (formerly known as Field Education) coordinates SBIRT training to align with the educational competencies graduate social work students are expected to obtain academically and in practice settings. Agency-Based Education seminars are held monthly for a total of three hours and are facilitated by full-time and adjunct faculty. The monthly seminars are held at different times and on separate days for first- and second-year graduate social work students, as the learning competencies differ in each year. All graduate social work students receive SBIRT training within agency-based education to prepare for social work practice in clinical, community, and advocacy roles addressing substance misuse. In addition, the Howard University Interprofessional Education committee, which includes the HUSSW, facilitates training sessions with graduate social work students, pharmacy, medicine, nursing, and occupational health students in conducting clinical assessments with standardized clients using the SBIRT process.

Course Integration

SBIRT has been endorsed by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) as an effective approach to training social work students to be responsive in identifying and addressing substance misuse. In 2008 and again in 2015, CSWE encouraged the integration of SBIRT in social work education, as SBIRT’s core competencies were linked to the Educational Policy and Advanced Standards (EPAS) established by CSWE (Council on Social Work Education, 2022). SBIRT training was found to have a positive impact on the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of students (Carlson et al., 2017; CSWE, 2022; Putney et al., 2017; Sacco et al., 2017).

A strategic process was employed to secure HUSSW faculty support and buy-in for SBIRT by initially identifying departmental champions. SBIRT champions included full-time associate professors and an adjunct faculty member. A facilitator’s training course during summer academic semesters was conducted by SBIRT faculty from HU-COM. HUSSW SBIRT champions received instruction on SBIRT as a clinical intervention tool and support in planning its incorporation into the MSW graduate program.

HUSSW faculty champions determined that agency-based education could provide a comprehensive approach to SBIRT integration, consisting of skills development and SBIRT applied in practice. Agency-based education instructors (field instructors) are trained in SBIRT to support the learning of MSW students while they develop social work practice skills in assigned local and regional agencies. An annual training for agency-based education instructors is conducted to ensure that the educational goals of CSWE and HUSSW are integrated into agency-based education practice and include SBIRT training. Agency-based education instructors are required to attend the annual training, and receive continuing education credits (CEUs). HUSSW SBIRT faculty champions also provide SBIRT training to our agency-based sites to further enhance the SBIRT learning experience of our students.

As a part of its integration efforts, HUSSW also incorporated SBIRT in several courses and professional development offerings. The “Substance Use and Misuse” course, which is offered in-person and online, includes a dedicated unit on SBIRT and its training components. Offered as a general elective, students can enroll in this course in the first or second year of the MSW program. In addition, the HUSSW Office of Professional Development and Continuing Education offers seminars in substance use and motivational interviewing, which provide students and faculty additional SBIRT training experiences. Professional development and continuing education seminars are held both in person and virtually. HUSSW utilizes Blackdr.org, an African American health organization that promotes cultural awareness and addresses health disparities, for additional professional development opportunities to address substance misuse and mental health through its online digital platform.

Guiding Philosophy

Agency-based education at HUSSW is guided by The Howard University School of Social Work’s Black Perspective, which is a framework for engaging in critical analyses of social issues and conditions that place African American and other communities in the path of oppression, marginalization, and structural racism. The Black Perspective emerged during the 1960s and 70s, and emphasized the importance of culture in assessing social conditions in Black communities. It shifted the focus from challenges to highlighting the strengths and positive attributes of these communities (Gourdine & Brown, 2016). An additional thrust of the Black Perspective lies in the understanding that individuals live within “intersecting environments” in their communities (Kondrat, 2013; Moss & Crewe, 2020, p. 78). HUSSW students are assigned to agencies in communities that experience the highest rates of health and social consequences of alcohol and substance misuse, particularly overdose and overdose deaths (Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, 2024), and whose constituents are often engaged in multiple systems of care.

The six principles of the Black Perspective are strengths, diversity, internationalization, vivification, affirmation, and social justice. SBIRT is an approach that fosters these principles as it is used in various community-based and clinical settings that serve minority populations. The structure of SBIRT allows for its rapid use in communities that experience the detrimental effects of substance misuse and marginalization. As a flexible intervention, SBIRT can be adapted to allow providers to have a broad reach in identifying substance misuse among populations that require cultural responsiveness.

Instructional Methods

Instructional methods that are used to conduct SBIRT training include didactics, clinical skills role playing, interprofessional simulation practice, and the use of SBIRT training videos. Didactic components include instruction on the background and history of SBIRT; information on SBIRT’s efficacy and results from evidence-based practice evaluations in medical, social work, and behavioral health settings; information on commonly used substances, prescription medication, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s low-risk drinking guidelines; and a review of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) criteria for substance use disorder and levels of severity based on the number of presenting symptoms.

The clinical skills component of the SBIRT training utilizes case scenarios that were developed to train students in cultural sensitivity and reflect the experiences of African American clients who interface with systems of care that address substance misuse. Students play the roles of both social worker and client, and receive feedback from the SBIRT faculty about general performance. Interprofessional education simulation is a clinical-skills experience that prepares social work students, along with students in nursing, medicine, pharmacy, and allied health, to screen and assess for substance misuse.

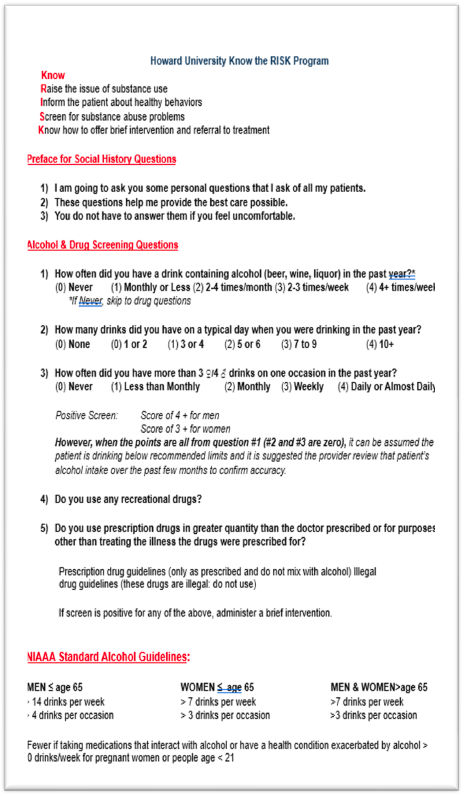

Through the HU SBIRT training program, graduate social work students are trained on the KNOW the RISK application, which emphasizes (R) raise the issue of substance use, (I) inform the client about healthy behaviors, (S) screen for substance use problems, and (K) know how to offer brief intervention (Kalu et al., 2016). The KNOW the RISK algorithm was developed by an interdisciplinary group of providers, including social workers, within Howard University to facilitate SBIRT training and prepare health and social service professional students to engage in culturally sensitive assessment and identification of substance use disorder. SBIRT faculty incorporate discussion and dialogue regarding barriers to screening for substance misuse, such as stigma, provider bias, and mistrust.

Figure 1

Know the Risk

Screening

HUSSW students are introduced to SBIRT screening by faculty during agency-based education seminars. Faculty emphasize the importance of standardizing SBIRT screening in the admission and intake process to assess alcohol and drug misuse. Instructions are provided to determine the level of risk and severity, which guides the type of intervention clients should receive. The National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA)’s Low Risk Drinking Guidelines and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)’s Quick Screen are reviewed as tools used for rapid assessment of alcohol and drug use to determine the need for further screening. Students receive an overview of validated screening tools that are commonly used in SBIRT, such as the AUDIT-C and the Drug Abuse Test-10 (DAST-10). In addition, the Cars, Relax, Alone, Friends, Forget, and Trouble (CRAFFT) screening tool, which assesses alcohol and drug use in adolescence, is also introduced to students. SBIRT faculty train students in interpreting the results of these validated screening tools and providing feedback to clients.

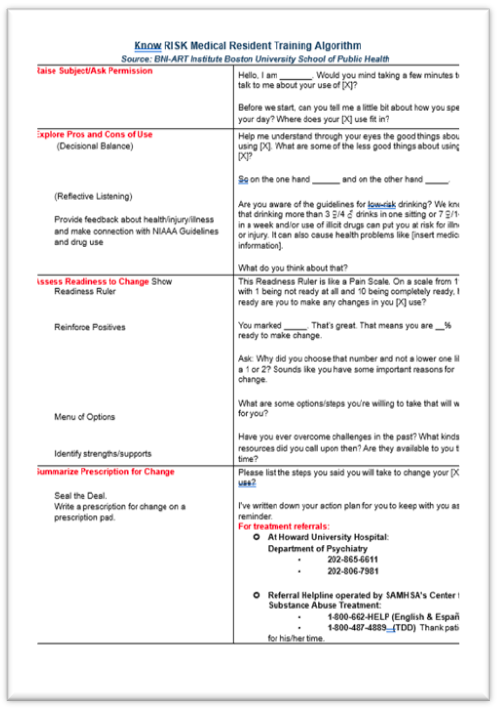

Brief Intervention

Brief Intervention (BI) prepares social work students to assist individuals in exploring reasons for change and to identify strategies that will support and facilitate their decision to modify or eliminate any unhealthy alcohol or substance misuse. Upon completion of the BI training, students can provide feedback on the risks associated with alcohol and substance misuse, engage clients in conversations about motivation for change, and summarize and collaborate on a change plan (Bernstein et al., 2007; Kalu et al., 2016). A case study accompanies BI training that includes cultural considerations such as health status, gender, socioeconomic status, and neighborhood characteristics, which reflect the person-in-environment framework, a key tenet of social work practice.

Figure 2

Training Algorithm, BNI-ART Institute Boston University School of Public Health

Readiness Ruler

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Motivational Interviewing

The change process that occurs during the BI is facilitated by Motivational Interviewing (MI). MI is a client-centered approach that is collaborative and renders mutual respect between individuals and their providers. Providers offer nonjudgmental support and guidance to the individual considering change (Miller, 2013). Studies have shown that MI is evidence-based and effective in promoting change with African Americans needing to modify health behaviors (Okoronkwo et al., 2021). The importance of culture is emphasized during MI training with MSW students, especially as students are working in systems of care that necessitate culturally responsive care to help African American and other minoritized clients discern willingness and readiness to change. Students are engaged in discussion and dialogue about how the role of culture fosters and facilitates the process of clients moving from a state of ambivalence to making informed decisions about wanting to make change that is congruent with cultural needs (Oh & Lee, 2016).

During the SBIRT training process, students engage in role-playing activities using a cluster of motivational interviewing tools to prepare for social work practice with clients who may exhibit ambivalence or resistance to change. The motivational interviewing tools include asking open-ended questions, providing affirmations, listening reflectively, and summarizing important statements from the provider–client conversation (OARS). MI training also includes teaching students how to assist clients who are ambivalent about their current situation and their feelings about exploring changes to alcohol or drug use. SBIRT faculty engage students in understanding the importance of assessing a client’s level of confidence and readiness for change, which can determine treatment success and outcomes (Gregoire et al., 2004; Heather et al., 1993; Opsal et al., 2019). Students are introduced to the Transtheoretical Model of Change (TMC), which explains the stages of precontemplation, contemplation, action, maintenance, and recurrence as individuals experience the process of change (DiClemente & Crisafulli, 2022).

Referral to Treatment

Referral to Treatment (RT) is the final component of SBIRT training at HUSSW. Integrating key social work concepts, particularly person-in-environment and the dignity and worth of individuals, students are instructed on the different types of treatment options available for alcohol and substance misuse and learn how to consider treatment options that can be facilitated within a supportive environment. Students receive information on the different types of treatments and how to make referrals, and gain skills to assist clients in choosing treatment that is aligned with their needs, including health, family, insurance, and family responsibilities. Similar to MI training, the RT training process includes SBIRT faculty reviewing the role of culture when assisting individuals in making decisions about treatment options. SBIRT faculty emphasize the importance of social workers assisting clients in navigating systems of care when engaged in referral to treatment.

Change Plans

Change plans are person-centered strategies that facilitate change and support a client’s efforts to reduce or eliminate alcohol or drug misuse. During role-playing exercises, students practice developing change plans that assist clients in exploring personal reasons for change and identifying options within their environment. Students practice offering suggestions to support clients’ decisions about change without imposing or forcing strategies on them. Students are also instructed to affirm the client’s strengths in their decisions for change. Since developing the change plan is the final SBIRT step, students are trained to engage clients in discussing the change process as a partnership, and in validating the client’s role along with the social worker.

SBIRT Practice in Agency-Based Education

The agency-based education seminar is interconnected with a social work field practice placement. Agencies with an affiliation agreement with the university provide students with direct, first-hand experience in social work practice methods. Instructors and supervisors are also trained in SBIRT, with the expectation that students will incorporate SBIRT into their training experience as they build and develop social work practice skills. SBIRT is not a requirement for agency-based education affiliates; however, it is expected that students will be provided support in identifying and addressing substance misuse, using agency guidelines and policies for referrals. As an integral part of the social work curriculum, agency-based education is where the application of SBIRT, along with the social and cultural tenets of the Black Perspective, is practiced to best prepare students to practice social work in underserved communities.

Future Directions

Preparing social work students at HBCUs in SBIRT builds the behavioral health workforce and increases the number of diverse providers of treatment for substance misuse. Training underrepresented social work students in SBIRT during their agency-based education experience equips them to engage in culturally responsive practice addressing disparities and systemic barriers for treating substance misuse in populations that have the greatest and unmet needs. Through SBIRT training, HBCU social students are able to contribute knowledge and skills to understanding the unique challenges of underserved communities that are overburdened by substance misuse and have the greatest need for treatment. Substance misuse should be incorporated as a required core subject in schools of social work to prepare students to recognize and identify indicators of substance use for early intervention and prevention. Individuals with substance misuse often interface with multiple systems of care in which social workers are service providers. SBIRT training components encompass common social work competencies and core values. Increasing the number of faculty trained in SBIRT and substance misuse widens the scope of social work programs to prepare students to serve across practice settings and decreases missed opportunities to address substance misuse. Future initiatives within HUSSW will include evaluating the level of satisfaction of students, faculty, and agency-based education instructors with the SBIRT training. An evaluation will also provide important information on how SBIRT training can be enhanced and improved to ensure alignment with education and social work practice training goals.

References

Ajluni, V., & Michalopoulou, G. (2025). Addressing the underrepresentation of African American mental health professionals: A call to action. Journal of Patient Experience, 12. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735241307382

Aldridge, A., Linford, R., & Bray, J. (2017) Substance use outcomes of clients served by a large US implementation of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Addiction, 112(52), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13651

Begun, A. L., Clapp, J. D., & The Alcohol Misuse Grand Challenge Collective. (2015). Preventing and reducing alcohol misuse and its consequences: A grand challenge for social work (Grand Challenges for Social Work Initiative Working Paper No. 14). American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare.

Bernstein, E., Bernstein, J., Feldman, J., Fernandez, W., Hagan, M., Mitchell, P., Safi, C., Woolard, R., Mello, M., Baird, J., Lee, C., Bazargan-Hejazi, S., Broderick, K., Laperrier, K. A., Kellermann, A., Wald, M. M., Taylor, R. E., Walton, K., Grant-Ervin, M., … Owens, P. (2007). An evidence-based alcohol Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) curriculum for emergency department (ED) providers improves skills and utilization. Substance Use and Addiction, 28(4), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1300/J465v28n04_01

DiClemente, C. C., & Crisafulli, M. A. (2022). Relapse on the road to recovery: Learning the lessons of failure on the way to successful behavior change. Journal of Health Service Psychology, 48(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42843-022-00058-5

DiNitto, D. M. (2005). The future of social work practice in addictions. Advances in Social Work, 6(1), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.18060/91

Carlson, J. M., Agley, J., Gassman, R. A., McNelis, A. M., Schwindt, R., Vannerson, J., Crabb, D., & Khaja, K. (2017). Effects and durability of an SBIRT training curriculum for first-year MSW students. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 17(1-2), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2017.1304946

Council on Social Work Education. (2022). 2022 educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs. https://tinyurl.com/4t8cbvhw

Coyle, S. (2020). The grand challenges for social work: An update. Social Work Today, 19(5), 16. https://www.SocialWorkToday.com/archive/SO19p16.shtml.

Estreet, A., Archibald, P., & Tirmazi, M. T. (2017) Exploring social work student education: The effect of a harm reduction curriculum on student knowledge and attitudes regarding opioid use disorders. Substance Abuse, 38(4), 369–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2017.1341447

Fisher, C. M., McCleary, J. S., Dimock, P., & Rohovit, J. (2014). Provider preparedness for treatment of co-occurring disorders: Comparison of social workers and alcohol and drug counselors. Social Work Education, 33(5), 626–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.919074

Ghonasgi, R., Paschke, M. E., Winograd, R. P., Wright, C., Selph, E., & Banks, D. E. (2024). The intersection of substance use stigma and anti-Black racial stigma: A scoping review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 133, 104612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104612

Gomez, E., Gyger, M., Borene, S., Klein-Cox, A., Denby, R., Hunt, S., & Sida, O. (2023). Using SBIRT (Screen, Brief Intervention, and Referral Treatment) training to reduce the stigmatization of substance use disorders among students and practitioners. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218221146391

Gourdine, R. M., & Brown, A. W. (2016). Social action, advocacy, and agents of change: Howard University School of Social Work in the 1970s. Black Classic Press.

Grand Challenges for Social Work (n.d.). History. https://grandchallengesforsocialwork.org/about/history/

Gregoire, T. K., & Burke, A. C. (2004) The relationship of legal coercion to readiness to change among adults with alcohol and other drug problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26(1), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00155-7

Halmo, R. S., Putney, J. M., & Collin, C.-R. R. (2024). Teaching note—Substance use education to improve harm reduction attitudes: Preparing social workers to advance public health. Journal of Social Work Education, 60(4), 618–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2023.2260843

Hankerson, S. H., Moise, N., Wilson, D., Waller, B. Y., Arnold, K. T., Duarte, C., Lugo-Candelas, C., Weissman, M. M., Wainberg, M., Yehuda, R., & Shim, R. (2022). The intergenerational impact of structural racism and cumulative trauma on depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 179(6), 434–440. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21101000

Heather, N., Rollnick, S., & Bell, A. (1993) Predictive validity of the Readiness to Change Questionnaire. Addiction, 88(12), 1667–1677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02042.x

Hughes, M., Suhail-Sindhu, S., Namirembe, S., Jordan, A., Medlock, M., Tookes, H. E., Turner, J., & Gonzalez-Zuniga, P. (2022). The crucial role of Black, Latinx, and Indigenous leadership in harm reduction and addiction treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 112(S2), S136–S139. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306807

Jordan, A., & Jegede, O. (2020). Building outreach and diversity in the field of addictions. The American Journal on Addictions, 29(5), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13097

Kalu, N., Cain, G., McLaurin-Jones, T., Scott, D., Kwagyan, J., Fassassi, C., Greene, W., & Taylor, R. E. (2016). Impact of a multicomponent Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) training curriculum on a medical residency program. Substance Abuse and Addiction Journal, 37(1), 242–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1035841

Kondrat, M. E. (2013). Person-in-environment. In National Association of Social Workers and Oxford University Press (Eds.), Encyclopedia of social work. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.285

Kourgiantakis, T., Sewell, K., & McNeil, S., Logan, J., Lee, E., Adamson, K., McCormick, M., & Kuehl, D. (2019) Social work education and training in mental health, addictions, and suicide: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 9(6), e024659. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024659

Lawrence, S. A., Cicale, C., Wharton, T. C., Chapple, R. L., Stewart, C., & Burg, M. A. (2022). Empathy and attitudes about substance abuse among social work students, clinical social workers, and nurses. Journal of Social Work in Practice in the Addictions, 22(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2021.1922038

Manuel, J. K., Satre, D. D., Tsoh, J., Moreno-John, G., Ramos, J. S., McCance-Katz, E. F., & Satterfield, J. M. (2015). Adapting Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) for alcohol and drugs to culturally diverse clinical populations. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 9(5), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000150

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd edition). Guilford Press.

Minnick, D. (2021). Examining substance use education in social work: A survey of MSW program leaders. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1671260

Moss, T., & Crewe, S. E. (2020). The Black Perspective: A framework for culturally competent health related evaluations for African Americans. New Directions for Evaluation, 166. 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20413.

National Association of Social Workers (2013). NASW standards for social work practice with clients with substance use disorders. https://tinyurl.com/mt54v2va

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (2024). Opioid-related fatalities: January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/2zdrymj7

Oh, H., & Lee, C. (2016). Culture and motivational interviewing. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(11), 1914–1919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.010

Okoronkwo, M., Vaughn, J., Bailey, R., Onor, I. O., & Ledet, R. (2021). Culturally sensitive application of the motivational interview to facilitate care for a Black male presenting to the emergency department with suicidal ideation. Clinical Case Reports, 2(5), 1–5. https://tinyurl.com/3ddb35w9

Opsal, A., Kristensen, Ø., & Clausen, T. (2019) Readiness to change among involuntarily and voluntarily admitted clients with substance use disorders. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 14(47). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-019-0237-y

Putney, J., Halmo, R., Collin, C.-R., Abrego-Baltay, B., O’Brien, M., & Thomas, K. A. (2024) The perceived impact of substance use education on social work students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Substance Use & Addiction Journal,45(3), 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/29767342241229051

Putney, J. M., O’Brien, K. H. M., Collin, C.-R., & Levine, A. (2017) Evaluation of alcohol Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) training for social workers. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 17(1-2), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2017.1302884

Russett, J. L., & Williams, A. (2015). An exploration of substance abuse course offerings for students in counseling and social work programs. Substance Abuse & Addiction Journal, 36(1), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.933153

Sacco, P., Ting, L., Crouch, T. B., Emery, L., Moreland, M., Bright, C., Frey, J., & DiClemente, C. (2017). SBIRT training in social work education: Evaluating change using standardized patient simulation. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 17(1-2), 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2017.1302886

Senreich, E., & Straussner, S. L. A. (2013). The effect of MSW education on students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding substance abusing clients. Journal of Social Work Education, 49(2), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2013.768485

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). The opioid crisis and the Black/African American population: An urgent issue. https://tinyurl.com/yckc59sz

Thoele, K., Moffat, L., Konicek, S., Lam-Chi, M., Newkirk, E., Fulton, J., & Newhouse, R. (2021) Strategies to promote the implementation of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in healthcare settings: A scoping review. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 16(42). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00380-z

Ting, L., Sacco, P., Gavin, L., Moreland, M., Peffer, R., Anvari-Clark, J., Tennor, M., Welsh, C., & DiClemente, C. (2023). Pre-training SBIRT knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of social work students and medical residents. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 23(4), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2023.2185993

Wacker, E., Rienks, S., Chassler, D., Devine, E. G., Amodeo, M., daSilva-Clark, M., & Lundgren, L. (2023). Research note—Online SBIRT training for on-campus, satellite campus, and online MSW students: Pre–post perceptions and practice. Journal of Social Work Education 59(2), 558–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.2019646

Wells, E. A., Kristman-Valente, A. N., Peavy, K. M., & Jackson, T. R. (2013). Social workers and delivery of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for substance use disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3-4), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2013.759033

Wilkey, C., Lundgren, L., & Amodeo, M. (2013). Addiction training in social work schools: A nationwide analysis. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 13(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2013.785872

Williams, J. H. (2016). Grand challenges for social work: Research, practice, and education. Social Work Research, 40(2), 67–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svw007